Review: Things Fall Apart

Author: Chinua Achebe

Author: Chinua Achebe

In the introduction of the book Biyi Bandele writes: ‘Reader, beware: Things Fall Apart is savage and tender; it blisters with wit and radiates with the inner glow of hard earned compassion. It is disillusioned but passionately engaged, solemn while being exuberant; it is polemical but wise. There is not a shred of congealed violence of cheap sentimentality: Achebe’s characters do not seek our permission to be human, they do not apologize for being complex (or being African, or for being human, or for being so extraordinarily alive).” And I believe there is no better warning to prepare one for the brilliance that this book exudes.

It is an unwritten and un-scientifically proven fact that there are books that a reader will come across in their short lived lives that will totally change their lives and alter the way they perceive reality; and that it is also true that once a reader comes across such books, those books will forever be imbedded in their souls and inhabit the deep trenches of their minds: only to be called upon whenever the wisdoms of their teachings are needed. For many, identifying such books is as easy as reading the first paragraph while for others they need to read and finish the book before its true nature is revealed to them: but with Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, the brilliance of the book is revealed as soon as the reader reads its famous opening paragraph.

Firs published in 1958, this book tells the epic tale of a once revered and feared man who, after having his life and the realities that made him who he was fall apart in front of his own eyes, resorts to the extreme measure of taking his own life as a last resort. The story is an almost poetic three part roller-coaster ride following the life of Okonkwo as he goes from a feared warrior in his village to being banned after killing a kinsman and to later him taking his life after seeing the world that he had fought to keep the same for so long and so hard die before his own eyes.

The first part of the story tracks Okonkwo’s life in his home clan of Umuofia. A man driven by the desire to be more than what his un-achieving father, Unoka, had become before he died, Okonkwo lives his life under the self-deteriorating emotion of fear – fear of becoming the mirror image of his father – and this ends up with him turning himself into a man whose actions are based on and acted out in fear and are therefore destructive: both to himself and to those he cared about. The reader is introduced to Okonkwo’s life and his patriarchal and almost sadistic views on life. A man who is consumed by a deep and destructive desire to become the greatest man in his village, Okonkwo’s desires and passions drive those closest to him – including his own son – to both despise and fear him. All seemed to be going well for him until one day he killed a kinsman and was therefore forced, together with his entire family, to be exiled from the village – or fatherland – for seven years.

The second part of the book tracks his life during his seven year exile which he spent in his motherland. It is during this time that things started falling apart for him not only in his mother land but also in the fatherland to which he had planned to return to after the seven years ban, and reclaim his position as a warrior. It was during this time that white people came into their lands and introduced to him and his people a new religion and government; to both of which he lost his oldest son. As a man who respected and practiced his tradition, this caused him great anguish. The people of his motherland did little to fight this new religion and he spent his days brooding over how life would have been different, and better, had he still been in his fatherland where men were more war-like; and would therefore not tolerate such things and fight and resist them. His seven years exile ended and he later moved back to his fatherland.

The third and final part of the book tracks his journey back to his fatherland. He goes back to his land of birth with the ambition of returning to his former glory and using his influence as a well-respected warrior to lead a fight against this new religion that was plaguing his land. He returns to his people to find them different from how he had left them. Like his son most of the people in the village had joined this new religion and, unlike how he had imagined, the people of the village were not doing anything to fight this religion that was taking away their people and turning them against one another. He was later part of a group of people that led a rebellion against the church and burnt it to the ground and was soon after arrested, together with other men, for their actions. After their release a meeting was called where Okonkwo hoped they would discuss a plan of attack; but he had already resolved that if they didn’t he would do so on his own and avenge the shame that was brought upon him by the church and its government. It was at during this meeting that he killed a messenger sent by the government to stop the meeting and, since he realized that his people were not planning to fight, he took his own life soon after.

The story is a story that, even though it as written well over 50 years ago, still finds relevance in the both the minds and lives of all those who are blessed enough to read it. It is a story that will never die: a story that will continue to live both in the minds and on the tongues of people for any generations to come. It is rare that an author writes a story that outlives them but with Things Fall Apart Chinua Achebe did just that. Few writers have managed to achieve the brilliance that Chinua Achebe achieved with this book and, from those who did, only a few did it deliberately.

Review: I Am Your Sister

Author: Audre Lorde

Edited by: Rudolph Byrd; Johnnetta Cole; Beverly Guy-Sheftall

For reasons too numerous to mention individually; with most, if not all, of those reasons being based on their uninformed, sexist and homophobic views – and were therefore invitations for me to also join them in their misogynistic tendencies – I have been “warned” by many black men to ‘be weary of these girls who call themselves feminists’, to quote one of them. ‘They are nothing but a bunch of angry girls who know nothing but male bashing,’ is what another one once said, but whenever I enquired as to where they get their information about these people they are so hell-bent on painting as evil I have never had any of them give me a source that I myself can check to corroborate their theories. Feminism is one of the most misunderstood theories I have ever come across and even though there is a considerable amount of literature on it, most people – especially those who are critical towards it, i.e males – have never read any of it.

There is a pool of individuals who have written some excellent work on feminism and the theories behind it, and within this pool Audre Lorde is considered to be one of those people who have shaped modern feminism thinking, ideology and pedagogy. “I Am Your Sister” is a collection of some of Audre’s published and unpublished work and allows us to take a walk in one of black feminism’s greatest minds. Published in 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc, and edited by RUDOLPH P. BYRD, JOHNNETTA BETSCH COLE and BEVERLY GUY-SHEFTALL this collection of Audres’ work is considered by many to be one of the most important pieces of literature on feminism.

The book contains four parts, with three of those parts – ‘From Sisiter Otsider and Burst of Light’; ‘My Words Will Be There’; and ‘Defiance and Survival’ – containing works, both previously published and unpublished, by Audre herself and the forth section – Reflections – containing work written by Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Alice Walker, Bell Hooks, and Gloria I. Joseph about Audre Lorde. The book contains a total of 24 essays, speeches and other work by Audre before she passed away in 1992. In these works Audre writes about her journey as a Black woman, a mother, a lesbian and a feminist and shows how even though those four tittles define her in different ways, she is never one of those things without being all of the others. She uses her amazing penmanship to highlight the struggles she faced as a Black lesbian feminist and how this not only adversely her but also how it adversely affected the Civil Right Movement together with the black lesbian and gay movement – with her being a key role player in both.

The brilliance of her work is made evident by the fact that she not only wrote these pieces as a black lesbian activist, but she also has pieces she wrote as a mother and woman who faced the same challenges that every other black straight woman faced in those days – some, if not all, of which they are still facing today. She highlighted the important role that every member of the black community – be they straight or gay – had to play in ensuring the liberation of all black people in both America and the world. The diversity of her work sets it and her apart from most writings and authors in black feminism and makes her more than just an academic commenting on a subject she studied; she wrote about her fears after she was diagnosed with cancer, and she also wrote about her optimism for the future after meeting black women across the world: teaching them how they can also play a role in the development and liberation of black people in their native countries and the world at large.

The collection has some amazing work by her but there are two specific ones that stood out for me: “Apartheid U.S.A” and “A Burst of Light: Living With Cancer”.

Apartheid U.S.A:

In this essay Audre discusses the plight of the black people across the world and how alienating the lesbian and gay community in the black community is more detrimental to its development and liberation than it is advantageous. The essay proves how well informed she is about the issues that black people across the world are facing and she shows how interconnected our struggles are with each other. She shows how being a lesbian and feminist does not stop her from being a black person and vice versa. It is a compelling read and it will open many people’s eyes to how there is no “us” and “them” in the black communities across the world.

A Burst of Light: Living With Cancer:

This is a collection of her diary inputs and tracks her journey of living with cancer. She documents her fears, her concerns and her trips across the world talking to black women about their development. She also documents her times spent teaching poetry in Germany and how that helped her while she was getting treatment for the cancer. In this collection she is not just an activist but she is a mother concerned about the future of her children, she is a friend thanking the support of her friends through her difficult times and she is a black woman concerned about the future of black women and people across the globe.

This collection of writing is one of the most insightful and educational work about feminism and the struggles that black woman and people from the LGBT community come across I have ever read+. It is by far a MUST READ – especially for those seeking knowledge about feminism in the black community.

Review: Native Life in South Africa

Author: Sol. T Plaatje

In any and all post-colonial countries in the world, the questions of land and the redistribution and restitution thereof are considered to be some of the most toughest and most debated questions after the independence of such countries; and the same can be said about South Africa. Together with the pivotal role it plays in the economic emancipation of the inhabitants, and most importantly the natives of such lands, land, in the words of Fanon, is one of the tools, if not the only one, that will bring such people, above all, dignity. South Africa, being the last African country to gain its independence from colonial rule, is a country that started these debates having had a pool of data from which they can extract lessons from other countries about which ways to go about answering the very tough question of how a government should fairly redistribute the land to its people without infringing on the rights of others.

But together with the pool of data which, if used correctly, can help bring change both faster and better came the fact that, since it was the last country to gain its independence – over 36 years after sdeGhana, the land in South Africa was in the greedy hands if colonialists for way too long and will therefore be very hard to regain and redistribute to the people of the country.

To gain a better understanding of the “land issue” in South Africa – like with many other things in life – it is very important that we look at and understand the history, and ipso facto the root cause, of this thorn on our side: and there is by far no better book I have ever come across that is better suited for this purpose than the book “Native Life In South Africa” by Sol. T Plaatje. This book, published in 1916 by P.S. King and Son, Ltd., London, is a thrilling firsthand account of the damages caused by the plaguing Natives’ Land Act that was signed into law in 1913. In it the author documents, as Brian Willan indicates in his introduction to the book, ‘the wider political and historical context that produced policies of the kind embodied in the natives act, and documents meticulously steps taken by South Africa’s rulers to exclude black South Africans from the exercise of political power.’

It is no hidden fact that ‘most black South Africans suffer from a very broken sense of history,’ as Bessie Head wrote in the foreword of the book. ‘[And] Native Life,’ she continued, ‘provides an essential missing link.’ In the book the author documents the history that led to the drafting and signing in to law of the treacherous Natives’ Land Act of 1913, and also traces the effects that that law had on the African people in South Africa. Even though he was a successful editor of a native newspaper, Tsala ea Becoana (Friend of the Becoana) – which was later renamed Tsala ea Batho (Friend of the People) – the author decided to write this book not as a passive reporter of the events that happened during and after the passing of the act, but decided to write it as an experiencer of its damaging effects. But because of his journalistic background, the book also possesses a lot of research and, as a consequence, is filled with facts and figures that the author uses to both substantiate his accounts and give it a “leg to stand on” if people were to ever criticize it and call it the work of an over imaginative mind.

The author also documents other important events that happened during the early 1900s: which include the formation of what is now the oldest liberation movement in the continent – the South African Natives National Congress (now called the African National Congress) – of which he was the founding Secretary; their failed attempt at finding assistance from the Imperial Government regarding stopping the suffering of the natives English subjects of one of His Majesty’s colonies due an unjust act passed by its’ parliament; he also documents the war between England and Germany and the effects it had on all of the English colonies – of which South Africa was the youngest member; he also documents the rebellious actions of the Boers against the English Imperialist government and their fight to make South Africa a self-governing and sovereign country.

The early 1900s were eventful times in South Africa and the Native’s Land Act of 1913 was but one of many other events whose effects we are still feeling today. It was during those times that South Africa unionized and the oldest liberation movement in Africa was born; and it was through this book that Sol Plaatje helped, through the written word, make these events both immortal and time transcending. This book is an important part of our country’s history and it gives a voice to a narrative of our history that has up to so far never been given a thorough listening to.

Review: Zenzele – Young, Gifted and Free

Author: Sandile Memela

Author: Sandile Memela

Besides The Price by Niccollo Machiaveli – which, if read subjectively, is easily identifiable as one itself – I have never been fond of reading self-help books. I have always detested how the authors of such books ignore the intersectional and subjective nature of the struggles and problems that people face; suggesting that all the problems of the world can and are solvable only if the reader follows a formula that they (the author) have been blessed enough to have in their possession and have conveniently penned down for the benefit of the reader and the world at large. After being labeled a lost generation for many years, many such books have been written for the benefit and consumption of the incorrectly appellated South Africa ‘born-frees’; and ‘Zenzele: Young, Gifted and Free’ by Sandile Memela is one such book.

Penned by one of South Africa’s most outspoken and critical writers, cultural critics and civil servants – and said by the author himself to be inspired by, and have its contents anchored in, the Black Consciousness ideology; culminating from ‘ a thought process that began in 1986’ – ‘Zenzele: Young, Gifted and Free’ is a seven chapter book by Sandile Memele in which he delves into is idea of how young people can adopt a new mindset about the struggles they face; and how they can make efforts to step towards using the power of their minds to ‘lose the apartheid baggage and to begin the journey from passive victimhood to being a full human being.’ Now, being a follower of the Black Consciousness Movement and strong believer in the teaching of more young Black people about its ideology, the prospects of coming across and reading a book written for the Black South African youth, which is inspired by, and has its contents anchored in the Black Consciousness ideology got me very exited; notwithstanding my knowledge of it being a self-help book from the onset.

The book is a compelling read in which, to deliver his message and lessons for the youth, the author uses his personal encounters with successful Black people (both young and old) during his time as a journalist and after and draws from their stories lessons about taking on a positive mental attitude that he wishes to impart and deposit into the mind of the reader. As a consequence – and philosophically embedded in the thread that keeps the book together – the lesson about the importance of the changing of the mental attitude of all young Black people who seek to accomplish anything in life transcends through every chapter of the book and keeps the reader engaged at all times. The author writes extensively about how within the attitudes of all the successful Black people he has ever come across there is s not-a-victim-of-my-past-and-circumstances mentality that they have used to find solutions for their problems and transcend to the apex of success in their respective fields.

But, like most self-help books, the book has its own faults.

The author, following a similar route as every other author of a self-help book, also ignores the intersectional and subjective nature of the struggles that the post independent black youth of South Africa have to face. He ignores that even though, generally speaking, every young black person faces the struggle for a better education and economic emancipation, a combination of their individual economic and social background; level of education; access to resources; gender; sexuality and many other factors contributes to each one of their struggles: and that because each and every one of their combinations is different from the next – in both the intensity and variation – a single solution would never work for all of them.

The author’s implication that the post-apartheid Black youth of South Africa have no business blaming apartheid for their struggles, and that the onus is on them and them alone to find a way out of these struggles suggest a sort of ignorance that the author has taken towards the structural and economic barriers – buriers that are still prevalent and functional today – that were put up to hinder the success of all Black people by the very apartheid system he is asking them to not blame. The author, drawing from his own personal experiences of overcoming hardships and becoming a success in life, makes the erroneous conclusion that if every young person followed in his, and the other successful people he makes mention of in the book, they will be guaranteed success – even if it is not to the desired level.

But together with its faults the book has some very inspirational stories about men and women who managed to make success of their lives under some of the harshest conditions imaginable. The author uses these stories to try and inspire the reader to look at their situation in a different manner, and even though that is a good thing, the fact that no heed or mention was made about the intersectional and subjective nature of all problems, this can be seen by many to be very problematic. It is a book that, because of the unconventional, unpopular and somewhat drastic suggestions it makes, needs to be read with the utmost care and open-mindedness.

The book is a definite read, if not for anything else, then for the inspirational stories and strong message found in between its two covers.

Review: The Un-Believer’s Journey

Author: S. Nyamfukudza

In every war or revolution there are always more fighters than just the ones who take up arms and fight. There are those who, in preparation for the victory they believe is eminent, take to educating themselves so that when the time comes for them to do so, they will be qualified enough to lead the country to new and greater heights. All the wars that have been posed against evil regimes with the aim of toppling them have had these two types of fighters, and in most cases, if not all, these two groups of fighters never seem to get along quite well. Before gaining independence in 1980, guerrillas in Zimbabwe (known as Rhodesia at the time) were engaged in a war to free their country from the evil Smith regime. With this war taking place, and victory looming near, there were members of the movement who believed that while others were busy fighting in the bush, the movement also needed members who will be ready to lead the country when the time came.

“The Non-Believer’s Journey” is a story written by S. Nyamfukudza and tells the story of a young teacher who, while wanting to join “the boys” in the fight, is taken aback by talks about tribal divisions that caused troubles for the fighters. Published in 1980, the story follows the life of Samson Mapfeka, a teacher in Highfields, Salisbury, who, because of his attitude and behavior towards the war, many might see as a traitor to the movement. After receiving a letter from his father about the killing of his uncle by “the boys” (as the guerrillas were called) after they were told that he was a sell-out, Sam sets out to go back to his village for his uncle’s burial; but the trip ends up becoming more than that. The story begins with the setting in Highfields where Sam and his friends are always finding solace from the war at the bottom of the bottle. Waking up after a heavy night of drinking, Sam decides to go back out for another round of drinks to ease his hangover before setting off for the village.

After having had a couple of drinks with his friends, Sam finally gets on a bus set for his village with nothing but the clothes on his back and some money for is sibling’s school fees. While on the way the bus comes across a road block where a young Afrikaaner soldier orders everyone in the bus to get off for inspection of their identity documents. After seeing that Sam was a teacher, the young solder decided to make some jokes about it to impress his older colleagues. No being in a mood to be made fun of by someone young enough to be his little brother, Sam decides to retaliate to the young solder’s mannerism, which only succeeds in angering the latter. Angry that a black person was speaking to him in such a manner, the young soldier decides to parade his power by ordering that Sam’s language be brought forth to be searched because of suspicion that he was actually taking supplies to the guerrillas that were in his village. Sam then informed the young soldier that he had no language and not believing him, the young solder ordered that all of the language be brought forth to be searched. While the language was being brought forth to the young soldier, a passenger wearing a white shirt decided to run away and the search was brought to a halt, and all the passengers were ordered back into the bus to leave while the soldiers chased the unknown man who escaped. All the passengers blamed Sam for the bad luck brought on that poor man who they suspected was taking much needed supplies for “the boys”.

Irritated by these developments in the attitude of his fellow passengers towards him for standing up for himself to a young man who had no right talk to him like that, and weary of walking after curfew after the road block caused them to run late, Sam then decided to get off the bus at a township near his village where he will spend the night and walk to the village in the morning when it was safer. It is in that township that he meets a young woman from his past, Raina, from whom he finds out that he is late for the funeral because it had happened on that day, and with whom he spends a drunken night making love to. The following day, after spending the day making love to the same woman, he made his way to the village to find the old men of his clan sitting together discussing the events that had happened. He joined them only to find that the family was still torn by the age old indifferences that have managed to tare his family apart. He later found out, to his disappointment, that one of his younger brothers had decided to leave school and join “the boys”. On his final night at the village the guerrillas decided to go to his village and the leader of the group called Sam aside to talk to him. He asked Sam if when he returned to the village he could bring them some medicine and, being aware of the danger the leader was asking him to put himself in, for a cause he didn’t believe in, Sam got into an argument with the leader which ended with the latter killing him.

The brilliance of the story comes from how the author tells of a side of the Zimbabwean people who, during a time of fighting and struggle, didn’t care much about taking up arms and fighting. He tells of a new generation of Zimbabweans who no longer believed in bullets and guns but believed in education, and the struggles that came from those who were fighting physically and those who were fighting using education. Sam was a young person who knew of the struggles that his people were going through but never took an effort to fight – be it politically or physically – and hid his shame by drowning his sorrows, not knowing, like Mr Mike Muendane would say, that sorrows can swim. It is a brilliant read and a definite age turner.

Review: Mayombe

Author: Pepetela

Author: Pepetela

We will never know the true consequences of war until the people who are most of the time left to die in the defense of an ideal – be it a good one or a bad one – cease to only be numbers on a report at the end of the war; numbers we proudly call “casualties of war”. Men and women, and in some cases children too, are called on by men drunk with power to defend “the pride of their land,” and are later called heroes for fighting in wars that most of them know nothing about. It is rare that men who are called to arms are done so for the right reasons but in the rare occasions that they are, it is even rarer for any of those men to want to relive those moments, in any way or form, post war. One man who was brave enough to pen down, in the form of an epic novel about the Angolan struggle, was Arthur Pestana dos Santos – better known by his pen-name Pepetela.

Born in Angola in in 1941, Arthur joined the MPLA guerrilla fighters in the Cabinda province in the late 1960. He served on the central front during the second liberation war and, in 1976 after Independence, was made Deputy Minister of Education. He later wrote Mayombe while he was serving in the MPLA in 1971. The book’s original Portuguese version was published 1980 under the wish of Angola’s first President, Agostinho Neto, because it is believed that he felt an open debate on the topics which the book deals with – the dangers of tribalism and racism – was one that needed to be “pursued in the wider context of independent Africa.” The book was first published in African Writers Series in 1983 and was translate from the Portuguese by Michael Wolfers.

Mayombe is a forest of Angola’s enclave province of Cabinda and it is set as the background, with an almost character presence, of the story. Mayombe (the book) tells the story of a group of guerrilla fighters for the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in the 1970’s, their time in the Mayombe forest, their rear-base and school at Dolisie in the neighboring Congo Republic, and the problems they had had to overcome both as a group and as individuals. The story begins with a scene in the Mayombe forest where thirteen guerrilla members were on a mission. We are first introduced to Theory – a mixed race teacher and political instructor at the base who is in constant fear because of his white ancestry. The Gabela born son of a Black mother and Portuguese father, Theory had always has felt that his white ancestry made it hard for him to identify with the struggles of black people and this has compelled him to make very rash and life threatening decisions. Racism had always been part of his life and his volunteering to join MPLA – and while there volunteer to do dangerous tasks – was a way for him to feel as though he belonged – and was no longer the maybe in a world of yes and no.

We are then introduced to Miracle – “The Bazooka-Man.” Born in Quibaxe – a Kimbundu area – Miracle is a man driven by tribalism. He believes that the Kimbundu tribe, which he, the Commissar and Operations Officer are part of, and because of their history as the most affected and “bravest” tribe in Angola, is the only tribe fit enough to lead the war against the colonialist. He believes that all men are equal, and should have the same rights, but that “all men are not at the same level; some are more advanced than others,” and that those who are more advanced [the Kimbundu tribe] should rule the others because “they are the ones with knowledge.” He believes that having witnessed his father’s head being taken off by a tractor qualifies him to become a leader in the rebellion and is disgruntled that instead of that happening he is subjected to “seeing persons who did not suffer” ordering them around.

The story then moves to a base set up by the guerrillas in Mayombe where “the men, dressed in green, turned green like the leaves and chestnut like colossal trunks.” It is here that we are introduced to another guerilla named New World. A highly politicized and theoretic comrade, New World chooses not to partake in the tribally influenced divisions that are strife in the camp. He looks at everything from a theoretical point of view and believes that the tribalism that has taken over the mindset of most of the guerillas is nothing but a waste of time. We also get introduced to Muatianvua who, like New World, does not wish to partake in tribally influenced divisions in the camp; even though his reasons for doing so are different from New World’s. As a well-travelled sailor in the African continent, Muatianvua doesn’t see himself as a member of a single tribe. He says; “from what tribe? I ask. From what tribe, if I am from all tribes, not only of Angola, but of Africa too? Do I not speak Swahili, did I not learn Hausa like a Nigerian? What is my language, I, who do not say a sentence without using words from different languages? And now, what do I use to talk to the comrades, to be understood by them? Portuguese? To what Angolan tribe do Portuguese belong?” (page 87). But even though divisions in the camp are visible and confrontations do come up, there are men at the camp who re dedicated to each member irrespective of what tribe they belong. One such man is the Commissar who, when sent to Dolisie on a mission to get more food for the base, gave up time with his fiancé while he was there because he wanted to make sure that his comrades didn’t go hungry.

The story then takes the reader to Dolisie where he is introduced to Ondine; Commissar’s fiancé. Taken by her desire for other men, she sleeps with Andre who is the leader of the Movement in Dolisie. Word of this reaches the camp and Commissar and the Commander make their way to Dolisie: Commissar to confront his fiancé and the Commander to take charge while Andre is taken to Brazzaille to face trail. The Commissar and Ondine end their engagement and the Commissar heads back to the camp to take leadership while the Commander remains at Dolisie. Ondine ends up falling in love with the Commander after spending many nights together with him. Later word arrives at Dolisie that the camp has been invaded and in acts of bravery many men from Dolisie put aside their differences and volunteered to go on a rescue mission to save their fellow countrymen. It was later established that there was a huge misunderstanding of events by VW (who was the young comrade who brought the news of the attack of the bade to Dolisie), and that, in-fact, the shots he heard were from Theory shooting a snake that seemed like it was attacking him. Nevertheless, this inspired a lot of confidence in the guerrillas and they set mission to capture a base that the enemy had set up that was very close to their base. We are also introduced to Stores Chief. A man who sternly believes in the revolution, Stores Chief is troubled by the tribalism that is crippling the movement and led to Ungrateful escaping from prison through the help of some of the guards.

An attack on the enemy base was set up and executed. We are here introduced to Struggle. As the only Cabinda born guerrilla in the MPLA, he is concerned that his people are not participating in the war that is meant to free them. He is aware of the suspicion in which his fellow fighters look at him but is thankful to have a Commander such as Fearless who sees beyond tribal lines. He and the Commander unfortunately meet their demise during the attack but their courage and self-sacrifice for their fellow fighters inspired a new attitude in the guerrillas. They both sacrificed their lives for members of the Movement and did so without taking heed to which tribe they belonged.

The story touches on issues like tribalism; religion; racism; and relationships between men and women, the leaders and the peasants, the movement and its members. It is an epic story filled with scenes of love, hate, fear, war, confusion and many other elements one never associates with war. The writer succeeded in turning men fighting in a war to save their country, men who one never sees them beyond just people carrying weapons, into men that we can all associate with. He turned them into more than just men carrying guns and thirsty for war. He turned them into men facing problems that each of us face in our daily lives and showed how they overcame them; giving them a live beyond just being numbers on paper. It is a story worth reading for anyone who is interested in seeing the other side of war: the human side.

Review: Efuru

Author: Flora Nwapa

Flora Nwapa is the second female Nigerian writer that I have ever read – the other being the more modern writer Chimamanda Adichie. As the first African female author to be published in the English language in Britain, I was immediately attracted to her work. She has published a number of other novels – which include Idu (1970), Never Again (1975), One is Enough (1981), and Women are Different (1986) – and she is said by many to have been a feminist writer even though she never identified herself as one. Efuru, which was her first novel, is a story is set in a village called Oguta in Nigeria – which is a village that Nwapa herself was born and lived in. Published in 1966 by Heineman in London, Efuru is a story about a brave, loving, caring, successful, and what one might call in modern terms feminist woman called Efuru. The story touches on a lot of issues but the one that is most prevalent, even if Nwapa would have disagreed, is feminism.

Not being very well versed about the feminist movement myself, to say that the Nwapa portrayed the main character of this novel in a feminist way would be to throw myself into waters whose turbulence I am not sure I will be able to handle, but it is a risk I am willing to take. Even though Nwapa openly said that she did not see herself as a feminist writer, her work on this novel, and on her other novels too, would make her sound self-contradictory if she said that in 2015. It is said that she did not identify herself as a feminist because of the belief that feminism was a practice left for white middle class women during her times, and she believed that to identify herself as a feminist would not be to identify herself with the issues of black women. Her portrayal of Efuru as a woman who defied patriarchy – and example of which was her act of marrying the man she loved without waiting for the consent of her father, or how she managed to strive for leadership in her community, would qualify her as a modern day feminist writer; if I ever knew one myself.

The story follows the life of Efuru and her journey as a woman in her village. It begins with her, daughter of Nwashuke Ogene – a man of noble parentage; a “mighty man of valour,” a man who “single handedly faught against the Aros” (an Igbo subgroup in Nigeria) when they went to molest his people; a man of many victories whom people say have never seen his back on the ground – marrying Adiza – a poor man from an unknown family who people never understood why a woman so beautiful, and is the daughter of such a prominent man, would choose to marry – despite not getting consent from her father and Adiza not paying the dowry he was expected to pay traditionally.

The book, notwithstanding the mentioning of things such as Christianity and modern medicine in some of the chapters, is set during a time when traditions were still held by the people of Oguta; a time when things like Nkwo day (which is one of the four days of the Igbo calendar) were still honoured and women “took baths” (or got circumcisions) with the idea that if they didn’t, their children would die young. Efuru, notwithstanding the fact that she and her husband diverged from tradition by marrying without following the ways of their people, organized to get circumcised before having her child in her first marriage in an attempt to keep tradition.

Though Adiza worked in a farm, Efuru traded in stall she owned in town. Her husband soon left the farm to join her in her business. Because the two had married without Adiza paying dowry to Efuru’s father, the two worked together to gather up enough money for the dowry. They managed to gather enough money and the process of paying the dowry was executed without any hindrance. After the dowry was paid two years went by without Efuru bearing a child for her husband and this caused her a lot of pain. She went to her father who in turn took her to a dibia (a traditional healer) to seek help. The dibia then gave her instructions on what she must do if she wished to bear a child and told her and her father that if she does those tasks without fail, she will bear a child within a year. Efuru obeyed the dibia and, as the dibia had said to her, she soon bore their first child – a baby girl – whom they named Ogonim. Efuru took care of her daughter well but she soon had to return to trading with her husband because they were losing money. She asked her mother-in-law if she could get her a maid who would help her with Ogonim while she went to trade with her husband. Omeieaku, who is her mother-in-law, found a young girl – Ogea – who was her cousin, Nwosu’s, daughter and even though it took her a while, Ogea eventually settled in with the family as she soon became a valuable member of the family.

Two years after their child was born, Efuru and Adiza started having problems in their marriage. Adiza would come during late hours of the night and some nights he wouldn’t even come home. He later went to Ndoni in the market to trade and Efuru later found out that he had gone there with another woman. Efuru spoke to her mother-in-law about her problems and that is when she found out the sad story of Omeifeaku’s past with Adiza’s father. Omeifeaku confided in her daughter-in-law and pleaded her to be patient with her husband. She told her about her patience with Adiza’s father and asked her to do the same with her husband. While this was going on and Efuru was contemplating leaving Adiza, Ogonim then got very sick. Ajanupu, who was Omeifeaku’s wise but short-tempered sister, did all she could to help Ogonim get better but the poor child soon passed on after she fell ill. Word was sent out for her father to return but, to the disappointment of his mother and wife, he never did. So Ogonim was buried without her father present for the ceremony.

After the burial of her daughter Efuru had to find a way to get back on her feet. She soon found her feet, through the encouragement of Ajanupu, and was soon trading again. She later decided that she would no longer wait for her husband to return and went back to her father’s house. After some time Ogea’s parents returned from the farm and soon after her father, Nwupo (Ogea’s father) became very ill. He was taken to a medical doctor who performed an operation, after which he became well again. Ogea’s parents got very happy at her father’s recovery and spent all of their money celebrating and forgot to pay back the debt they owed to Efuru so they could get their daughter back. Two years later Efuru met another man, Gilbert, who proposed marriage to her which, after thinking it over, she agreed to do. Four years went by in Efuru’s new marriage and she bore no child for her new husband. This caused problems in her marriage and her new mother in law asked her to do something about it; lest she wants her husband to take a new wife who will give him children. Efuru took these words to heart but instead of going to a dibia, like she did in her first marriage, she decided to go to a medical doctor. She later learned that Umhari (the Goddess of the great blue lake) had chosen her to become one of her worshipers and this was confirmed by a dibia that was called by her father to interpret the dreams she had been having about meeting a woman at the bottom of the lake. Efuru ended up agreeing to find a second wife who will bear children for her husband and she and her mother-in-law decided to marry a young woman by the name Nkoyeni.

Efuru was hit by another tragedy when her father suddenly passed away. The whole village was sad at the passing of Efuru’s father and they mourned him deeply. Despite the expectation for him to be present at his wife’s father’s funeral, Gilbert did not come for the burial Efuru’s father and that as the beginning of the problems of their marriage. Four months went by and Gilbert returned to his wife. Soon after Efuru turned sick and there were rumors that she had committed adultery and in order for her to be better she needed to confess. Her husband also accused her of adultery and that was the end of their marriage.

Because of the era in which it was published, I believe Nwapa also wanted to show, through the story, a time when there was a major cultural and traditional change in the lives of the people of Nigeria. This is made evident by the by the choices of that people started making in their daily lives: choosing to go to a medical doctor instead of a dibia, choosing to practice Christianity instead of their pagan beliefs, young people starting to ignore certain practices and beliefs of their people, and the mention of people attending school (in order to do which one had to become a Christian first). This is a wonderfully captivating story.

Review: Devil on the Cross

Author: Ngugi Wa Thiong’o

Many who have taken the time to research about colonialism, imperialism and their subsequent impacts on the lives of the African – with imperialism still finding its way through the cracks purposely left open by the new leaders – will know how crippled these two phenomenon have left many Africans, and how much they still do, even though one has been “defeated” and the other we are told is not in existence. One could have read a countless number of books about these two phenomenon and their impacts on African lives, but they will surely find that none come into comparison with this work by Ngugi; and many who have read any of Ngugi’s work will agree that many of his work tend to leave that type of effect on people.

In this book Ngugi has once again achieved the feat that many African authors have been known to be good at; fictionalizing reality. He tells the story of the defeat of colonialism by the people of Kenya and its replacement by imperialism. The crucifixion of the “Devil of the Cross”, which the reader is introduced to very early in the book – chapter two, by “people dressed in rags” is a metaphor for the defeat of colonialism in Kenya by her people, and the subsequent taking down of the very same devil, after three days, by people “dressed in suits and ties” is a metaphor for the introduction of imperialism by money hungry people who were in leadership positions in Kenya and her capital.

The story is what can only be described as an African tale full of proverbs and fables told by a man who had a deep knowledge of his people. It is about a young woman, Wariinga, and her struggles as a young person in Kenya. The story begins almost tragically with young Wariinga, having been kicked out of her apartment, being fired for refusing to sleep with her boss, and breaking up with her young lover because he suspected that Warringa had slept with her boss to get the job to begin with, deciding she wanted to end her life. She made her way to town, where she planned to execute her intentions, but as she was about to “she heard a voice in her head: why are you trying to kill yourself again? Who instructed you that your work here on earth is finished? Who told you that your time is up?” and this was the turning point of her life.

A young man saved her from being killed by a bus driving towards her and, to some level, became the starting point of what turned out to become a journey that this young woman didn’t expect she would ever have to travel. After their encounter, the young man gave her an invitation to a “Devil’s feast” that was to be held the following day in Illmorog, Warringa’s home town; to which she was travelling that very same day. The feast was to celebrate “modern theft and robbery” and it was to be attended by modern thieves who would compete for seven positions to be given to the winners by an international delegate in their companies; so these thieves can be the front men in their companies while the delegates rake up all the profits.

On her way to her home town in “Matatu Matata Matamu Model T Ford,” she met other people – Mwaura, Gatuiria, Wangari, Muturi, and Mwireri – who also become central to the story. Some of these people were also heading to the feast – some to participate and others to just witness – while others didn’t even know of its existence. They ended up all going and the story that follows is one filled with lessons about Kenyan history, the history of the Mau Mau and the liberation of Kenya from colonialism and their fall into imperialism.

Ngugi was always known as a man who was critical of his government and those in power and this book was written while he was in detention after being detained by the end of 1977, the year his controversial play “I Will Marry When I Want” came out. Kenya, at the time this book was written, was a country fresh out of independence; having gained independence from Britain on Dec. 12, 1963. As a country fresh out of the clutches of colonialism, Kenya was a country still trying to find her feet, which proved to be a hard feat with corrupt leaders. The Kenyata government was filled with corruption and the wealth of the country was in the hands of a few politically connected individual while the ordinary citizens were living in horrible conditions. This book is Ngugi’s use of fiction to critically dissect those conditions and tell the stories of the ordinary people of Kenya.

Very few people can produce, with the same level of brilliance as Ngugi Wa Thiong’o did during those days, work of this nature. This is the work of a brilliant writer who knew his subject matter very well, and never deterred from his convictions.

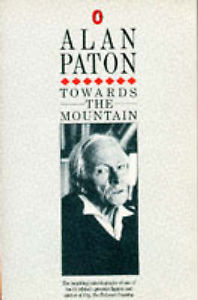

Review: Towards the Mountain

Author: Alan Paton

Author: Alan Paton

It seems only yesterday that I was sitting in a room with magnificent souls listening to artists from across Soweto talk about their passion for the art. Then one of those artists, a female dancer whose name I do not remember, asked me which field of art I was in and it was only when she asked this question that I realised that I have never had an answer for it. Whether this was because I did not know the answer to the question, or because I had not yet acquired the vocabulary to express it in, I do not know, but I had a very difficult time answering that question. It was only a week later, when I came across the book “Towards the Mountain” by Alan Paton that I began to understand what “my art” really was.

‘My art,’ if anyone can call it that, is enjoying art. I spend most of my time consuming the products of artistic minds like those of Alan Paton and it is books like “Towards the Mountain” that prove this definition of mine true and make me enjoy what I do even more. Like many of the books that I have read so far, “Towards the Mountain” is a book I came across by pure chance. The name Alan Paton, before my encounter with this book, was one I usually came across in the past but didn’t mean much to me. It was one of those names that everyone knew but I never took interest in getting to know myself; which is something I now look back on with great regret.

An autobiography of Alan Paton, “Towards the Mountain” is one of the most poetic and captivating bodies of work I have ever had the pleasure of reading. First published in 1980, this book takes the reader into the life of one of the most celebrated and world renowned South African writers of all time. Only describable as a guided tour by the man himself into the life of an impeccable wordsmith, this book takes you on a journey into the life of a man who had the awe inducing ability to put into words the world as he saw it to be; and what was more was that he managed to do this without sounding like a man chronologically reporting the events that transpired in his life.

In the book Alan Paton earnestly writes about his life as a man who was driven by a passion to serve others. He begins the book with telling the story of his life as a young person growing up in Pietermaritzburg, Natal. He writes about the passion for liberty and freedom – which he derived from the despise he acquired as a young man of his father’s use of violence to assert authority – that consumed his life as a young man growing up in a strict Christadelphian family. A lover of literature and a man with a command for the English language that always leaves one in total awe, all of these recollections are done in one of the most poetic and, to some extent, simplistic ways I have ever come across, and I believe this is one of the things that makes this book so special.

He continues by describing his years as an English speaking white man in South Africa and all his encounters with different people from different ethnicities and races in both his university and post-university life. A section of his life that had the biggest impact for his latter career as a writer, and which he spends a tremendous amount of time writing about – chapter 18 to chapter 23, and he continues to mention it in the subsequent chapters – is the time he spent as the principal of the Diepkloof reformatory. He writes that it was some of the experiences he had during those 13 years of his life that influenced a lot of his writing, and that some of the storylines and characters for some of his writing – including for his world renowned novel “Cry, the Beloved Country” – were inspired by the people and the events of those years. He writes:

“It was inevitable that the reformatory would play a great part in the story [Cry, the Beloved Country], and equally inevitable that the city of Johannesburg and the far distant country would do so…”

As you go through this poetic journey into this man’s life you will be confronted by the idea that Alan Paton was a man in constant battle with the emotional conflicts caused by the state in which race issues were in in the country at the time. He was constantly trying to figure out his role in the betterment of the country, and he found some guidance through his religious life. Some of the people he interacted with also played a major role in shaping his ideology and developing his role as a member of society who will play out his role in the development and betterment of his home country.

One major lesson that I picked up from this book – which I doubt he intended to deliver with through book, not that I believe he had any lesson he was trying to deliver through the book anyway – was that if the African community does not begin to tell its own stories they will be lost forever. I came to this lesson after reading parts of the book where Alan himself describes how little he knew of the African community. This became clear when he writes: “why a delinquent boy from a derelict home should have come to cherish, almost fiercely, such qualities as punctuality, reliability, loyalty, and honesty I do not claim to understand” when he was describing an African boy in the reformatory who turned out to become an outstanding member of his community.

He was a man who believed that all people were equal and even wrote many stories about the injustices that African people went through during those times, but the one thing that made him different from many people who did the same thing during those times, and many who do the same thing now, is that he was aware of his lack of knowledge about the everyday lives of the people who were the main subjects of many of his works. He was a man who knew his role and played it to the best of his ability and this book is a deeper look into that truth. It is a brilliant read and a must read for all South Africans.

Review: Treasure Island

Author: Robert Louis Stevenson

It’s very rare that a person ever comes across books that he has spent most of his life thirsting to read. As a lover of literature, one is bound to, at some point in time, come across names of books whose legend has transcended time and are engraved in the walls of the literature hall of fame. Books that have graced the shelves of many great men, and will continue to grace the shelves of many more people for generations to come.

One such book is Treasure Island by the Edinburgh born author Robert Louis Stevenson. I’ve spend years hearing about this book from a wide range of sources that include other books, movies, and other avid readers and since my first encounter with its name, it has become a book that I have always wanted to get lost in. But, as fate would have it, my journey to Funda Community College has once again given me a chance to read one of the books that I have always wanted to read.

I came across this book while I was going through a pile of books that were gathering dust in the small rooms of the Es’kia Mphahlele Library, in which they have been forced to find a new home, trying to find African Literature books. I decided to start reading it and as soon as I began reading it became very hard for me to stop. Even though I had a tough time reading and understanding the pirate/buccaneer colloquial used in some of the dialogs in the book, I thoroughly enjoyed the adventures the book took me on and all the wonderful characters it has.

The book tells the story of young Jim Hawkins and his adventure to Treasure Island. The story begins with Jim and his family’s encounter with Captain Flint. A buccaneer who has buried treasure and is fleeing from his old shipmates, Captain Flint one day walks into the Admiral Benbow inn, which is both run and owned by Jim’s parents, and decides to settle there while on his flee. His shipmates eventually locate him and succeed in killing him, with the hope of finding the map to his hidden treasure. But instead of the buccaneers finding it, the map was found by young Jim, who in turn took it to Dr Livesely.

The doctor decided to contact Mr Trelawney and ask him to organize a voyage to the treasure bearing island, which the later did very well. Mr Trelawney organised a ship for them – the Hispaniola – and all the hands that were needed to ensure the success of the trip. In the crew were former shipmates of Captain Flint who, under the leadership of John Sliver, planned to ambush the crew and take all the booty of the voyage.

The adventure that follows includes gun fights, tropical island scenarios, the digging for the gold, fights between the good and the bad guys, and many other scenarios typical of a bad guys verses good guys adventure. The story ends with the good guys wining and John Silver escaping after he had been accepted back into the Hispaniola after saving Jim’s life more than once. The surviving members of the voyage return home as men of wealth and some spend their money wisely while others spend it carelessly, “according to their nature” as Jim put it.

The book was written in first person, with Jim Hawkins as the narrator, and reads more like an adventurous autobiography than a fictional story. It is a brilliant book for young people, but is also a good read for older people, and is a book that you would read if you wanted to escape the real world into one full of adventure. Once you turn the first page it will be very hard for you to stop reading, and even though the fact that you would have to familiarise yourself with buccaneer colloquial adds a bit of extra work for the reader, that process itself also adds a lot to the books adventure.

The book is a definite must read and I definitely enjoyed reading it.